Section by Tyler Simpson. In memory of Stu Tanquist, resting in power.

Every person living unhoused or in an informal settlement has a unique experience, and it’s important not to generalize this broad range of situations in a way that defines people under stigmatizing language, such as the characterization of “the homeless” that we often see. Many advocates working in housing justice prefer using language that describes an individual’s situation, such as “unhoused,” “sleeping in a shelter,” “living at Tent City 3,” etc., over language that paints such a broad stroke to sum a person up as “one of the homeless.” A great deal of housing insecurity is not visible. We also need to affirm that everyone, no matter their criminal record, substance use, or mental health, deserves the human right to housing.

“Housing is a Human Right, Without Housing People Die”

In “Homelessness, Rights, and the Delusion of Property,” geography Professor Nicholas Blomley of Simon Fraser University argues that houselessness is a result of private property, taking away the right to the city from some. They write, “For conservatives, the homeless are people who have made bad choices. For progressives, they are victims of structural forces that drive them into poverty.” Neither understand that homelessness does not exist because of any individual’s situation, but because private property rights give some the ability to control and others must abide. Blomley quotes Waldron, an earlier geographer on the unhoused, who stated that for them, private property creates, “a series of fences that stand between them and somewhere to be, somewhere to act.” Housing insecurity is generated by the same system of capitalism that has created climate change and threatens the sustainability of human society. Private property is the existence of fences that allow some people to dominate and destroy the environment, without any democratic process to regulate it, and keep other people unable to find even a place to sit.

With the tech boom, the housing crisis is the reality of Seattle. Since March 2012 median rent has increased by 68%, from $1,757 to $2,586 (Zillow, 2019), and the number of people living unsheltered outside has increased from nearly 2,600 in January 2012 to over 6,300 in January 2018 (Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, 2018). Many voices on the local extreme-right aim to paint a myth that this human rights crisis is the fault of generous services they assume Seattle has, despite the vast majority of unhoused people in Seattle losing housing while living in Seattle, while others make the Victorian-age judgement of those experiencing substance addiction and mental health crises as being the “undeserving poor,” fighting tooth and nail against accommodating ‘low-barrier’ housing that can offer life-saving sanctuary for people the wealthy find more difficult to empathize with.

It’s crucial to remember that the Housing Crisis began in Duwamish Territory with its European colonization. Just ten years after the Duwamish Nation signed the Treaty of Point Elliot, the Seattle City Council’s 1865 Exclusion Act stated:

“Be it ordained by the Board of Trustees of the Town of Seattle, That no Indian or Indians shall be permitted to reside, or locate their residences on any street, highway, lane, or alley or any vacant lot in the town of Seattle.”

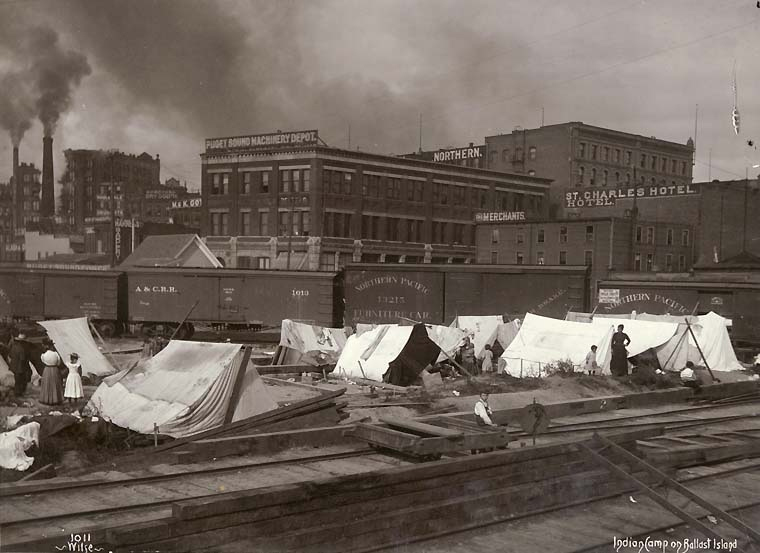

In the following decades, violent arson committed by real estate developers burned long house villages across the city, including at the Duwamish River and along Lake Washington where U Village now stands. Ballast Island, an artificial island made of rock, hosted a tent city of displaced Duwamish refugees beginning in 1885. By 1910, US Bureau of Indian Affairs official counts estimated between 1,000 and 3,000 houseless First People in Seattle. Indigenous people continue to be disproportionately impacted by houselessness in Seattle, despite having the most valid right to this city. (Gwinn, 2007)

With growing industrialization, Single Room Occupancy Hotels developed across Seattle’s downtown, Pioneer Square, and Chinatown-International District, offering 20,000 dorm-style homes up to the 1980s. 183 of 300 SRO buildings were owned by Japanese-American families prior to their incarceration in World War II, leading to their seizure by white speculators that often acted as ‘slumlords,’ deferring essential maintenance and giving little regard to the residents that were largely immigrants of color, Indigenous, and working-class. In 1949, units without their own bathroom and kitchen were declared ‘substandard’ by the federal government, and prevented from getting financing that would be used to pay for maintenance. As fire safety concerns developed alongside Neoliberalism in the 1970s, Seattle began systemically shuttering the densely populated buildings. Seen as curing “blight,” 36% of buildings were replaced with parking lots to serve the increasingly suburbanizing middle class, eliminating housing altogether from Downtown. UC Berkeley professor and author of literature on SROs Paul Groth said to Real Change, “The crisis in residential hotel supply is a planned event, a function of local, state, and federal policies that have encourage housing for some types of people and reduced supplies of housing for others.” The gentrification made way for a high-end Downtown shopping district, Benaroya Hall, and now high-rises even in the International District. Prior to these demolitions alongside President Reagan’s War on Welfare that cut Housing and Urban Development funding from $30 to $7 billion, people sleeping in the rough was rare and practically newsworthy in Seattle. (Griffey, 2001)

Globally, informal settlement residents are most vulnerable to the effects of climate change (Williams). The fringes of cities, from Seattle’s SODO to Manilla, are usually in floodplains and industrially polluted areas that cause health conditions. Seattle’s authorized and unauthorized encampments should not be decontextualized from global informal settlements. They’re equally a result of a lack of affordable and social housing, face the constant displacing effort of the state and capitalism, and their residents feel the effects of the climate more directly than anyone while having the least carbon footprint. Additionally, we’re entering an era of climate refugee crisis, and Seattle’s moderate climate, hills that protect from sea level rise, and lack of draught will certainly make it a necessary city for additional migration and growth of vulnerable populations, yet we’re not even prepared to suitably house existing residents.

Blomley, N. “Homelessness, Rights, and the Delusions of Property.” 2009. Urban Geography, Volume 30, Issue 6, p.577-590.

Williams, David S., Costa, Mariá M., et al. “Vulnerability of informal settlements in the context of rapid urbanization and climate change.” Jan 2019. Environment & Urbanization. Institute for Environment and Development.

Griffey, Trevor. “A Prologue to Homelessness.” Nov 2001. Real Change Newspaper. Volume 8, No.23. pg. 2, 8, 13-15. Available online: https://www.realchangenews.org/sites/default/files/20011101-MT.pdf

Gwin, Mary Ann. “Native landscape: The rich layer of indigenous history under Seattle’s skin.” Aug 2007. The Seattle Times. Available online: https://www.seattletimes.com/life/lifestyle/native-landscape-the-rich-layer-of-indigenous-history-under-seattles-skin/

Zillow. “Seattle Home Prices & Values.” Retrieved Mar 11 2019. Available online: https://www.zillow.com/seattle-wa/home-values/